Since the 1990s, Regional Growth Centers (RGCs) have played a central role in the growth strategy of the Puget Sound region. There are now 29, along with nine manufacturing/industrial centers (MICs) and other local or county- designated centers. Centers are a mechanism to focus growth and prioritize transportation investments. But the performance of centers is varied. Some, including the six centers in Seattle and downtown Bellevue, have far outperformed others where growth is anemic or non-existent.

This has prompted a revisiting of the regional center system that recognizes variations between centers. The Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) has released a draft proposal for comment (through November 8). It envisions a two-tier system of ‘urban’ and ‘metro’ centers. Metro centers must meet more stringent criteria. They should have existing density of 30 activity units (population+employment) per acre, vs. 18 for urban centers. Planned targets are also higher at 85 activity units vs 45 for the urban centers. Transit service at metro centers should generally be light rail or equivalent BRT, whereas frequent bus service may suffice for an urban center. That threshold would designate ten metro centers in King County, and one each in Pierce, Snohomish and Kitsap Counties.

Beyond the regional growth centers, there are new criteria for manufacturing and industrial centers (MICs) which will also see a two-tier classification. The MICs process creates a new path for designating MICs, not only recognizing the largest centers, but also preserving industrial land from encroachment. There is a more consistent process for countywide centers, where King County currently has stricter standards than other counties. There is recognition of military installations. Military bases operate outside regional plans, but several are large enough to have important transportation impacts.

Updating standards for centers across four counties is politically fraught because every city is closely watching the prospects for their local centers. The King County centers (81% of center employment, 78% of center population) are far ahead of their suburban counterparts. The PSRC disburses $250 million in transportation investments annually, and the suburban counties wouldn’t stand for such a lopsided share of funding.

To avoid disruption to underperforming centers, several compromises have been made to delay impacts. The preliminary framework does not recommend revisions to the funding priority for different types of regional centers at this time. Neither is there any imminent prospect of de-designating existing centers. The first evaluation of existing centers will take place in 2018-2020 as part of the VISION 2040 update. Centers have until 2025 to achieve consistency with new standards, and the PSRC board has flexibility in evaluating existing centers after 2025 if they are close to meeting the criteria.

How imbalanced are the centers? A background report prepared by PSRC staff in 2016 offers some highlights:

- Many places that are not designated centers have denser activity than some centers. Ballard, downtown Kirkland, and the Highway 99 corridor in Edmonds and Lynnwood, all have denser activity than the majority of existing regional growth centers.

- Several centers have activity levels too low to qualify for regional center status under the current minimum criteria of 18 activity units per acre. These include Bothell Canyon Park (14.0 au/acre), Lakewood (15.9 au/acre), Puyallup South Hill (10.4 au/acre), and Silverdale (13.1 au/acre).

- Other centers already far exceed the future planned densities of other centers. These include South Lake Union (115 au/acre), Bellevue (129 au/acre) and Seattle Downtown (194 au/acre).

- Regional growth centers vary greatly in their roles as concentrations of employment or population. Federal Way, Issaquah and Tukwila all have little or no residential population.

- The scale of the centers varies widely. The four contiguous centers in Seattle (Seattle Downtown, First Hill/Capitol Hill, South Lake Union, and Uptown) have a combined 320,000 population and employment. This is 80 times larger than the smallest RGCs.

A more aggressive policy, though politically impossible, would more quickly redirect spending to centers with concentrated growth in King County. The new centers framework is, at least, an opportunity to gradually realign transportation investments to the fastest growing centers in future.

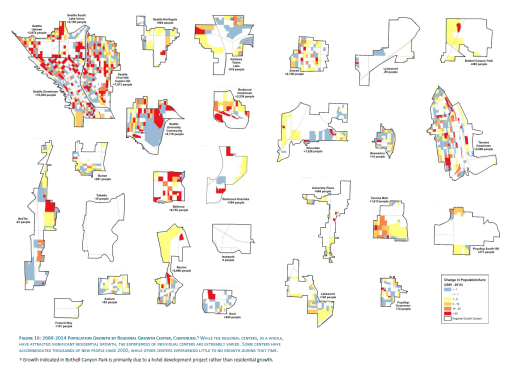

Update: When interpreting the charts, note the chart at top and population chart below are for 2000-2014, but the jobs chart at end is 2010-2014 only.

what is driving the loss in employment in Downtown Seattle? That surprised me.

Actually, the two charts contradict each other. What gives?

Yeah — something is amiss. On the first chart, they show a loss of 15,930 jobs. On the second chart (the one that shows just jobs) they show +14,709 jobs. So it isn’t just a matter of flipping the sign — something weird is going on with the charts.

That’s not the only example. First Hill/Capitol Hill also doesn’t line up (+1,191 versus -2,607).

The time frames are confusing. The first (blue/green) chart is for the period 2000-2014, as is the second chart (population). But the last chart (jobs) is for 2010-2014.

So Downtown Seattle jobs have a bad decade 2000-2010 (WaMu, Great Recession), and a rapid pickup after 2010.

OK, that makes sense. It does say that, I just missed it.

based on how small the squares are it could be the completion of a construction site before people have move in

Yeah, I was thinking that, but it still doesn’t explain a big loss of jobs over a 14 year period. For the most part, smaller buildings are being replaced by bigger ones, so even if a couple buildings are torn down, one new building that has been completed would make up for it.

I suppose it could be a big statistical anomaly that was the result of bad timing. We weren’t quite back to peak employment in 2014, but were building like crazy. A lot of lots that sat empty through the beginning of the recession were being constructed, but hadn’t been completed. New ones were just starting (and workers were kicked out — maybe to South Lake Union).

I would be very surprised if this is still the case (my guess is downtown employment has gone way up).

Because the region is a long, north-south shaped geography with major physical constraints to the east and west, I keep wanting to see how balanced our employment and populations are to the north and south of our high employment areas in Seattle and maybe Bellevue. That may be more important than an individual regional growth center when defining investments.

I think a very credible case could be made to recognize the profound shift in regional land use growth that is going to happen as a result of ST3. Rather than have just these amoebic growth centers, we should have a new and different focus on station areas (pedestrian districts) — enhancing our region’s recently pledged commitment to fund a high-frequency rail network (not assumed in the last update).

I think that is putting the cart before the horse. There are many places (First Hill, Fremont, Central Area) that weren’t involved in the ST3 (or ST2, or ST1) discussion but are growing like crazy, while other places (Fife) won’t grow much at all, even when the train gets there. What is clear with this report is that the PSRC has over committed to suburban areas, as has ST3. As I said below, it is a reasonable assumption, it is just horribly out of date. There is no great move to the suburbs (for jobs or housing). It is the opposite, and the planning and investment should follow suit, and figure out how someone in, say, Edmonds, can get to his job in Fremont.

ST3 is a good analogy. The legacy centers process is over-suburban because the suburbs demand it even though few of the distant centers are performing well. Unlike ST3, Pierce and Kitsap have the option of simply walking away from PSRC, and getting their own federal transportation funds. That’s why it has been impossible for King County to push as hard as they otherwise should on reforming the centers.

I think the PSRC is simply out of date. They haven’t accepted the changes in office development that have occurred over the last 30 years. Companies are moving away from lonesome suburbs to downtown centers in the big city (Seattle) or secondary, but very close cities (Bellevue, Oakland, etc.). Employment is also growing in secondary neighborhoods within big cities. Places like Ballard, Fremont, Wallingford and the UW have all seen substantial office growth, despite being pretty far away from downtown, but well within the old city. It is a trend that will likely continue.

It’ll be interesting to see if this trend shifts as prices spike in Seattle & East King, for both housing and office rent. Just this month, the PSBJ front page article was about how South King is primed for growth as both developers and renters seek out more affordable places to build, work and live. In Issaquah, the city commissioned a study to try to understand why multi-story mixed use wasn’t being built, and the economists came back with the conclusion that in Issaquah – unlike Seattle, Bellevue, and Redmond – the average rent $/sq ft wasn’t yet high enough to offset the higher cost of building a VMU building. Under the current rapid growth in rent, they projected that VMU development would pencil out in central Issaquah in 5~10 years.

I know this is shocking for someone who lives in Seattle, but in a place like, say, Auburn, rents might not be high enough for it to make financial sense to built a brand new 5 story apartment, even if it’s immediately adjacent to a train station.

Also, secondary cities are doing a better job of understanding that both residents and employers want more urban places, and places like Burien, Shoreline, Lynwood are both re-zoning and spending on infrastructure and amenities accordingly.

Keep in mind the massive growth in office space in Seattle is really being driven by one thing – Amazon, particularly after the recession. If Amazon ceases to expand in a few years, the pace of growth in Seattle should level off. I think as long as the regional economy is red hot, I think we’ll see these secondary growth center start to show some actual growth.

Auburn’s train station is only useful if you are commuting to Seattle in the peak period.

Most likely, anyone living in such a building in that location brings a car with them. So, now the building is all the more expensive because it includes parking.

Thus, part of the economics is also what would have to be built to meet the market demands there. A five floor building with parking is going to cost a lot per actual living unit, and probably winds up being two or three floors.

>> I think we’ll see these secondary growth center start to show some actual growth.

Oh yes, definitely. My point is, though, that they will still lag the secondary growth centers that exist in the city. Places like Ballard, Fremont, and even Lake City and Rainier Valley will grow first. Meanwhile, the primary growth centers like the UW, downtown Seattle (defined so broadly it includes Capitol Hill and Lower Queen Anne), and similar spots on the East Side will all grow faster than those suburban growth centers. It is pretty much exactly like you said — you have to get to the point where the other places are just too expensive before building in the suburbs becomes really attractive. By this very definition, it means that more people want to work in the city.

This wasn’t always the case. Suburban office development came into being for a couple of reasons. One is cheaper land, certainly, but also the belief that folks just wanted to live in the suburbs, and could live close to their work. Neither is true anymore. Suburban living is less popular, and trying to build a point to point transportation system to support it is very difficult. You can get from practically anywhere to downtown, but getting to a suburban office space is difficult (you either fight traffic, or spend all day on the bus). Even if you do prefer suburban living, chances are, your spouse won’t. With an increasing number of two income households struggling just to make ends meet, expecting both to work in the same suburb is just unrealistic. If you really are trying to move to where the people are, then it makes sense to locate within walking distance, not driving distance. This means someplace like Lower Queen Anne. One person walks to work, while the other catches a bus downtown.

Then there is the coolness factor. Obviously fashion changes over time, but when the first office parks were built, people probably thought they were spectacular. Huge plazas, maybe even a pretty forested walkway — quite tranquil, really, and I’m sure appealing for many. But now folks want to be able to walk out there door, grab some Nepalese food, and maybe stay after work to catch a show in the evening. That just won’t happen on a corporate campus.

It all adds up to more urban areas being more popular.

This post pretty explains why I don’t take PSRC seriously.

Finally the PSRC recognizes that some urban growth centers have been irrationally ignored, like the federal non-recognition of some Indian tribes including the Duwamish. Although the primary blame lies with King County which refused to recognize Ballard and Lake City because they didn’t have enough zoned jobs under its formula and their high performance in housing and better housing:jobs balance didn’t count. The new formula sounds significantly better. But it’s coming a little late. We should have done this ten years ago before we decided where to put the largest transit investments we ever made or probably will make.

My guess is Ballard employment is similar to Northgate employment. Not huge for Seattle (or Bellevue) but way bigger than most of the suburban centers. Northgate and Ballard are similar in terms of employment — some retail and a lot of medical. Lake City really doesn’t have that many jobs. It does have some, just not a lot. They are all pretty big in terms of population, and likely way bigger than most of the suburban centers.

Focusing on centers is fairly problematic. Ballard is adding jobs and people, as is Fremont. Lower Wallingford has now gotten into the game. None of them are as big as the UW, or downtown Seattle (or downtown Bellevue) but they are all bigger in population than most of the suburban centers, and probably bigger in employment. Do you treat them all as being part of the same mass (Ballard-Fremont-Wallingford) or separate centers? I think if you treat them all as being part of the same group, it would be a typical physical size, but one of the bigger “centers”. For example, this: https://drive.google.com/open?id=1tH6fjenCKM9aLYP87dTfhKcaRTDw9dUi&usp=sharing is weird in terms of shape, but not that weird, and certainly not that big for being a “center” (roughly two square miles). But you have way more people working and living within that area than most of the other “centers”.

Ballard-Wallingford are really one large urban village because they run together, and a significant chunk of the activities are on 36th-Leary Way. I’ve argued that the natural unit is Ballard to University Village. That would be similar to the size of Chicago’s North Side which is a very successful. Your map shows that what’s blocking it: zoning and nimbys in Wallingfrord.

Well, I suppose I could go all they way to the U-Village. I figure the UW is so much bigger than the rest of it, though, that it makes sense to just split it. As far as zoning in Wallingford is concerned, I did follow that, for the most part. But if you look at what actually exists, there are a lot of multi-plexes in Wallingford, unlike the area to the east of the UW. Density is fairly decent, as a result (unlike Laurelhurst). For the most part, my map tried to focus on both population and employment density, as opposed to just the former. If it was the former, I would probably just include everything south of 65th. Then the only problem is the industrial “beer zone” in “Frelard” (between Market and Leary and between 15th and 8th). Industrial jobs tend be fairly low density, and housing is low density as well.

“Transit service at [urban] centers should be light rail or equivalent BRT, whereas frequent bus service may suffice for an [urban] center.” – one of those should be a metro center, I think the former?

Thanks! Fixed.

Can we have a graph showing how many of those jobs pay their employees enough money to live in Seattle? And how many people who used to be able to live in Seattle have had to move to lower growth area- which should also being affecting growth there?

And how many people will have to move again as their own forced dispersal spreads rent-rises exponentially? And what will be the effect on transit of these extremely fluid forces. Safe to say we’ve never seen anything like this confluence of forces.

But to me, first is most important. For exact reason that nobody answers, or even asks it. Comments?

Mark Dublin

I think that part of the issue is that at least for the cities in East King (Bothell, Kenmore, Kirkland, Redmond, Bellevue, Woodinville) the priority is downtown revitalization. Redmond and Bellevue have overlapping downtowns and growth centers, which works out well (especially Bellevue). Kirkland and Bothell have to deal with downtowns far away from their supposed growth centers. Yet while DT Kirkland and Bothell are walkable and are getting more and more apartments, the growth centers are sprawling environments with huge parking lots and horrible side walks.

Watching a debate between the Bothell city council candidates recently, the message from everyone was “Downtown is doing great – we’re rebuilding everything, more apartments, etc…etc… But we don’t know what to do with Canyon Park. We should invest, but don’t know how.” Totem Lake is not a good example of what to do and hopefully the same thing won’t happen at Canyon Park.